- Home

- Columnist

Why a recent Southasian film festival in Lahore felt like a pet goat about to be sacrificed

KT NEWS SERVICE. Dated: 10/31/2023 7:14:58 AM

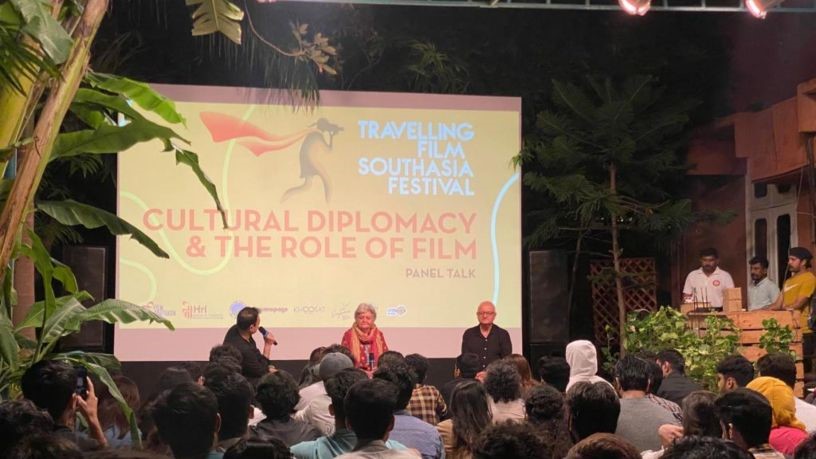

The concluding session: Sarmad Khoosat, Salima Hashmi and Kanak Mani Dixit. Photo by Maryum Yousaf

What do festivals like the Travelling Film South Asia Festival from Kathmandu mean for Pakistan, which has a history of aborted film festivals? Going to this festival, which took place after over two decades, I felt like the little girl in one of the films who tries to save her pet goat

By Ahmad Bilal

LAHORE: As a young professional in Lahore over 20 years ago, I remember a short documentary, Cricket Lives in Lahore (2000), screened in Lahore under the banner of the Travelling Film South Asia Festival from Kathmandu.

The documentary, by the filmmaker Farjad Nabi, had the most thrilling footage, innovative frames and sharp cuts – hard to achieve back then with the VHS technique. I believe some ad campaigns of leading multinational brands took inspiration from the film and used similar imagery, locations, and treatment while showcasing cricket fever in Pakistan.

This year marks the silver jubilee of Film South Asia, held every two years in Kathmandu. Over the past 25 years, the festival has screened films around the entire South Asian region. But in Pakistan, it was screened only for a couple of years, including the edition I remember.

The Travelling Film South Asia Festival took place in Pakistan after a gap of over 20 years. It felt a bit nostalgic because the Nepali journalist Kanak Mani Dixit, the founder of the festival, was in town, and of course, Farjad Nabi, who was involved in the earlier editions.

Rarity in Pakistan

Such festivals are a rarity in Pakistan. But when they take place, they are enormous crowd-pullers. Several such events became defunct after running for a few years – like the Matteela Film Festival, organised by Farjad Nabi and his team, or the Kara Film Festival, organised by the journalist Hasan Zaidi in Karachi.

For many years, the renowned Peerzada family’s World Performing Arts Festival in Lahore a series of international festivals that began with the First International Puppet Festival in 1992 and held almost every year until 2007. The Rafi Peer Theatre Workshop (RPTW) also initiated Youth Theatre Festivals in 1999, which provided opportunities to various amateur groups and performing arts societies of educational institutes to explore and showcase their talent to a larger audience.

In each case, these festivals have been initiated by individuals passionate about the arts, organising them on a self-help basis, with scanty or no official support. As a result, it was not sustainable over time.

Meanwhile, a new series of festivals cropped up, like the international theatre festivals organised by the National Academy of Performing Arts (NAPA) over the past decade, with a break during the challenging times of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Literary festivals have also been taking place regularly since 2010, starting with the Karachi Literary Festival developed along the lines of the Jaipur Literary Festival. The Lahore Literary Festival began in 2012, followed by Islamabad Literature Festival in 2013.

The Children’s Literature Festival, rebranded as the Pakistan Learning Festival, has been running since 2011. It has developed a sustainable model through crowdsourcing and sharing human and monetary resources.

Emotional experience

I felt highly emotional as I headed to the Travelling Film South Asia Festival in Lahore, held at Olomopolo Media, a studio-like space next to a large hospital near the Chinese consulate and close to Punjab University’s New Campus.

One Olomopolo hall seats 30-40 spectators, and a ‘dalan’ or open courtyard seats 70-80. A food court has seating arrangements for interval popcorn and cold drinks. The place remained packed throughout the festival. There were young people, reflecting a new generation of moviemakers – and the Lahore audiences’ thirst and aspiration for collective cultural experiences.

The sacrificial lamb

The festival included the 20-minute-long feature Eid Mubarak, a live-action short film from Pakistan, distributed by the New Creator streaming platform. It revolves around a six-year-old girl, Iman, who, with the help of her elder sister, Momina, is on a mission to save her beloved pet goat from being sacrificed on the Muslim festival Eid al-Azha.

The most challenging part of the film may have been the representation of the story of Prophet Ibrahim (on Him be Peace) or Abraham in the Judaio-Christian tradition and his beloved son. The filmmakers managed the challenge with some basic animation, careful not to offend religious sentiments since representational images of holy persons are taboo here.

The mother narrates the story to her daughters about how the son to be sacrificed is miraculously saved as a goat sent from heaven replaces him. When the daughters ask the mother if she would ever sacrifice them, the mother’s slight pause before shaking her head in the negative is the highest plot point, appreciated by the audience with an audible reaction.

The end credits feature a photograph that inspired the story which many in Pakistan will be able to relate to – two little girls in their Eid finery, standing in front of their family’s beheaded goat on Eid al-Azha in Karachi, Pakistan, in the early 2000s.

To me the film is an allegory of the near-surrendered status of Pakistan’s cultural activities, theatre, and film festivals. Iman loves her goat but it is about to be sacrificed. Similarly, the youth love a phenomenon but before it reaches its potential, it is compromised, prohibited, and often outlawed for mostly unknown reasons.

Thus, we find terms like “Pakistan’s first ever …,” or “The country’s only …,” as cultural activities remain in a perpetual state of a new beginning.

I belong to a generation that enjoyed music concerts, cricket and hockey matches in huge, crowded stadiums. Theatre or film festivals were a new phenomenon in Pakistan in the 1990s. They provided a whole new idea of collectivity, transnationalism, and the importance of diversity. They also provided innovative ways of looking at entertainment and economy and helped us build our soft image in the global world.

I would always go to the festivals in Lahore, participate in whatever way I could, and loved them as six-year-old Iman of Eid Mubarak loved her pet goat, not knowing that no miracle would take place to save them.

A conversation

On the last weekend of September, on the concluding night of Travelling Film South Asia, the space was packed for the panel session with Lahore-based artist and educator Salima Hashmi and journalist Kanak Dixit from Kathmandu in conversation with filmmaker Sarmad Khoosat. They talked about the collective stories and experiences that travel beyond borders.

Art and film have been facing a lot of control, said Salima Hashmi, suggesting that “artists and filmmakers should be dheet (resilient) and chalak (smart) to play around the censor policies.”

Maybe the organisers of such festivals also need to play chalak and coin some new terminologies. In a postcolonial society with a tinge of religion, words have complicated connotations; thus, terms like film, performing arts, music, dance, and theatre are more threatened and vulnerable than the words; learning, literature, education, digital, moral, mystic and sufi.

It gave me some hope that literary festivals will survive and keep growing consistently. However, postcolonial societies have a history of banning writers and thinkers, and in Sufic tradition, they can always translate: “Ilmo Bas Kari O Yar” as “No more education, please.”

Kanak Dixit talked about the love rooted in the people across borders and noted the connectedness of stories around the region. Audiences in Kathmandu can relate to films from Lahore, and moviegoers in Colombo resonate with films made in Dhaka.

“Our stories are more connected to the people of Southasia rather than the Western spectators,” he said.

“Southasia is a big market, and it should be open to all the creatives of this region,” he added. The Travelling Film Festival’s prime focus is to develop a platform that can freely show stories across borders.

Discussion moderator Sarmad Khoosat highlighted the brighter side – he appreciated how so many people supported the arts by contributing online to his film Zindagi Tamasha after he released it on YouTube.

The award-winning film Pakistan’s entry to the Oscars in 2021 had been banned before it could be released in Pakistani cinemas. However, the considerable interest generated after Khoosat participated in a fundraiser for the South-Asia Peace Action Network encouraged him to post it to YouTube, where it garnered over three-quarters of a million views in less than a month.

“I feel glad to share that young filmmakers are making films all around Pakistan,” said festival organiser Farjad Nabi, responding to an audience question.

The festival showcased films like B For Nao, a story from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, The Secret Life from Hunza, and Shikaaf Bar Noor from Quetta.

Young filmmakers from all around Pakistan are making films to tell their stories, and they should have the opportunity to release these to a larger market.

As the film festival concluded in Lahore, I felt like a 6-year child wanting to save her pet goat.

Next stop: Gujranwala

The Travelling Film Festival then went to Gujranwala for a day – the first time a film festival was held in an educational institute in that city. The venue was The Learning Hub (TLH), a private women’s college affiliated with the University of the Punjab. Over 300 college students got to see the best film of the festival Taangh (Longing), by Bani Singh, along with two short films. Their social media posts showed their involvement, zeal and excitement. Maybe the event felt like a pet goat for these students.

On the last night, Punjab University’s newly formed Music and Performing Arts Department hosted an evening in honour of the guests from Nepal. The students presented music and theatrical pieces under a banyan tree, associated with wisdom, expansion and eternal life within the historical context of Indus Valley and Southasia.

It feels like something precious is happening to my society, something loved by the youth. Such events may be typical in other cultures.

One day, perhaps Pakistan will achieve that normalcy, and such cultural events will continue and become regular features. Maybe also, one day, academic and administrative bodies will support and sustain such cultural events regularly.

If this happens, it will be a true contribution on the cultural, creative, and economic front. Students of music and performing arts, film, fine arts, and design, and researchers from Pakistan’s art institutes will be facilitated and encouraged to engage freely in artistic and creative activities within Southasia.

A well-connected and bonded youth of the region can ensure a much happier, more creative society and contribute to a better future.

Prof. Dr. Ahmad Bilal is Director, Postgraduate Research Center of Creative Arts, University College of Art & Design, University of the Punjab. He holds a PhD from the School of Art & Design, Nottingham University, U.K.. Email ahmad.bilal2010@my.ntu.ac.uk , ahmad.cad@pu.edu.pk.

*Southasia: Borrowing from Himal Southasian, Sapan uses ‘Southasia’ as one word, “seeking to restore some of the historical unity of our common living space, without wishing any violence on the existing nation-states.”

This is a Sapan News syndicated feature.